There is weather. And sometimes, there are other things.

January 2018: What does model "guidance" mean to you?

For 10 years now (God I'm #old), I've participated in the University of Oklahoma WxChallenge forecast contest. Since I've been a professor, I've used it as a teaching tool in my senior-level Advanced Forecasting courses. Although I have found myself personally spending less and less time on my WxChallenge forecasts, I always check the forecast distribution each day to see what consensus is and what other forecasters are thinking. Over the past 1-2 years, I've noticed there is often a major disconnect between what I *think* consensus will be and what it actually ends up being. And it made me think...since most of the forecasters in the contest are current university/grad students, are people using very different tools than I am these days?

The answer to this question is likely more complicated than a single post can discuss and varies widely. With all the nice-looking forecast model websites and #prettycolors out there these days, it's easy to be overwhelmed by the amount of available data. But I think it's fair to wonder if the definition of model "guidance" has changed. Throughout my education, my forecasting professors and mentors always taught me that model data was best thought of as "guidance" or a starting point. It is then the job of the human forecaster to adjust "guidance" based on their expertise. Precipitation forecasts are a whole other can of worms, but for point temperature forecasts, we were always taught that Model Output Statistics (MOS) should be that "guidance". Since WxChallenge is point forecasting, I will focus on that here.

Long story short, MOS is a statistical post-processing technique that takes operational model data (e.g., NAM/GFS) and uses multiple linear regression to incorporate additional and/or observed data. NWS has a nice overview of what MOS is here. Historically, there are a couple of large advantages to using MOS guidance for surface temperature forecasts as opposed to raw 2 m model temperatures:

- Parameterizations. Essentially, surface fluxes are hard. Models do not handle solar heating or radiational cooling all that well and many of these processes are parameterized. Newer models are better at these things, but it's still an issue.

- Data. MOS incorporates station climatological data as well as prior observations, in addition to the latest raw model output. In this regard, MOS is often described as having a "memory", whereas raw model data does not.

To be honest, I rarely look at raw model 2 m temperatures when I'm forecasting. It's not how I was taught, and it's not what has worked for me. But the first week of WxChallenge this Spring semester forecasting for Austin Texas (KAUS) made me think "am I increasingly living in my own forecast universe?" (don't give me that look, peanut gallery)

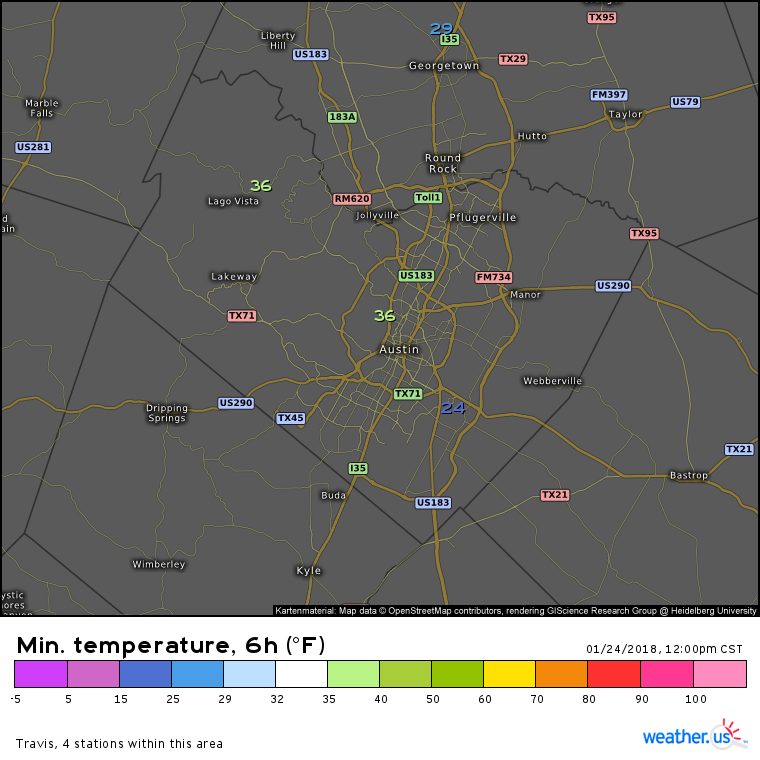

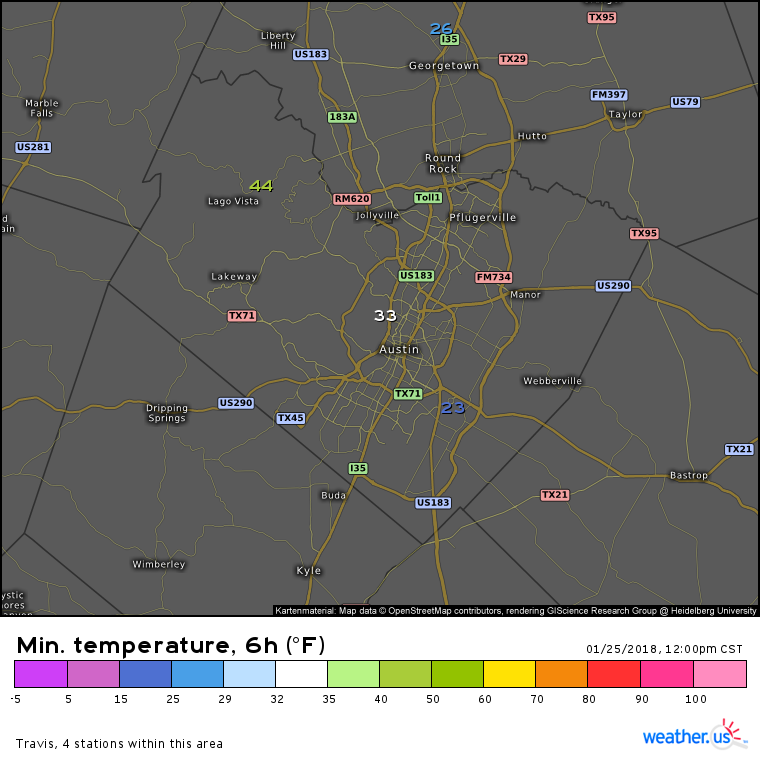

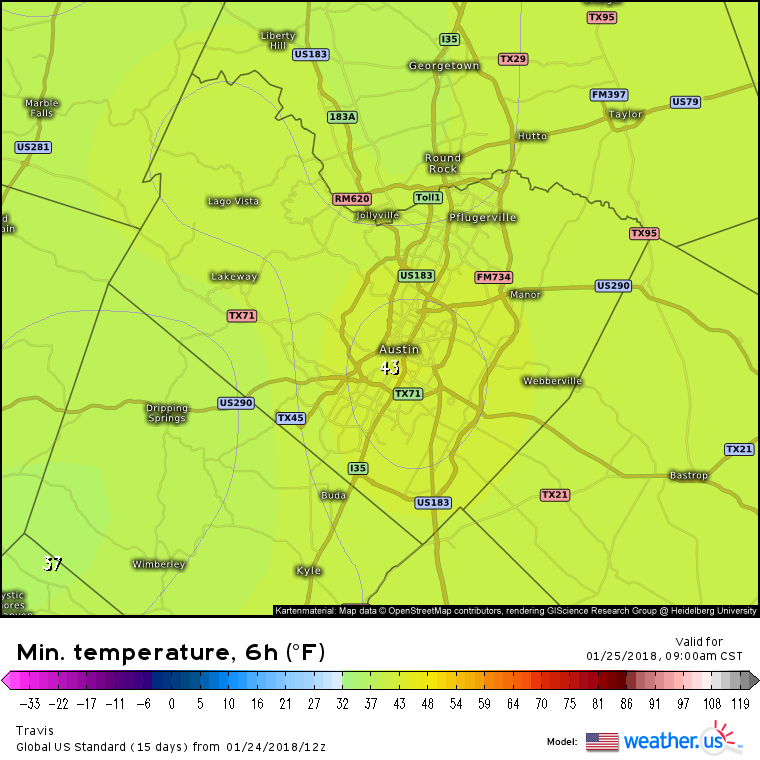

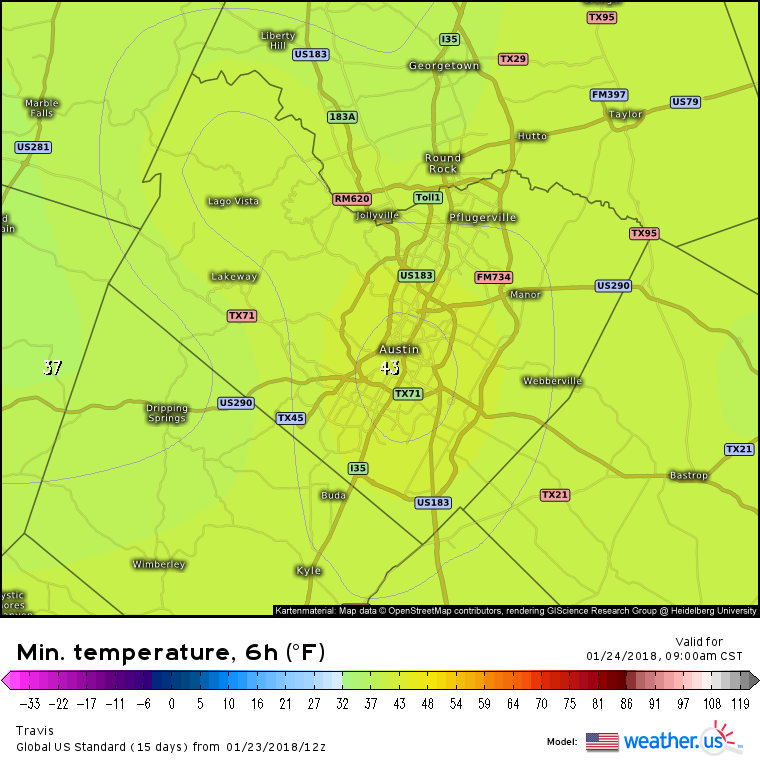

In order to illustrate my point, I'm going to focus on the minimum temperature forecasts for Days 2 (24 Jan) and 3 (25 Jan) at KAUS. One of the interesting things about this location is that the airport is located roughly 8-10 miles outside the city on the east/southeast side. Having just been there for the AMS conference, I can tell you that as you drive from downtown toward the airport, the environment quickly goes from very urban to quite rural. Days 2 and 3 were both calm and clear nights, ideal for radiational cooling. Below are the minimum temperature observed values for each night, with the plots from Weather.us. The min temp on Day 2 was 24, while on Day 3 it was 23 (values in blue to the southeast of the word "Austin"). You'll notice that there was a striking 10+ F temperature difference between the rural airport location and the urban environment closer to downtown.

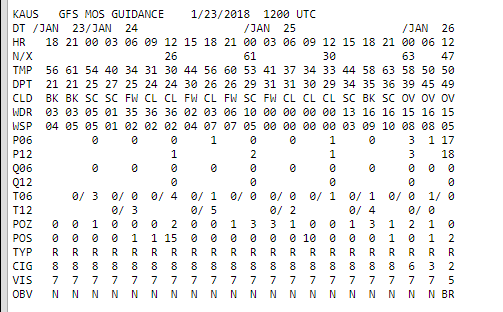

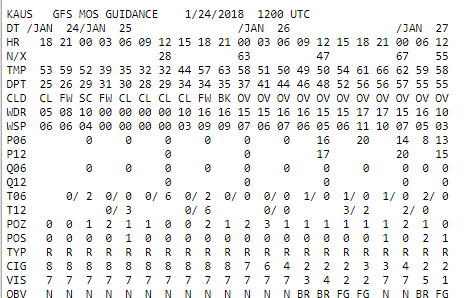

The next question is "did the models forecast this?" And the answers seem to depend strongly on what you consider to be a "model forecast." MOS, especially the GFS MOS, mostly *did* see it coming. Below is 12Z GFS MOS from the days our forecasts were due. For Day 2, the MOS had 26 and for Day 3, the MOS had 28. Now your reaction, particularly for Day 3, might be to say "well okay but it still was too warm." And while that is true to some extent, consider what the raw 2 m model temperature forecasts were showing.

Below are 12Z GFS 2 m minimum temperature forecasts for Days 2 and 3. You will notice that not only were they too warm, but they were too warm by at least 10-12 F. And the differences between the urban and rural environments were not large enough. This was not unique to the GFS; the ECMWF and NAM had similar issues each day. It's one thing to miss a temperature forecast by 2-5 F; 10-12 F is a whole other level.

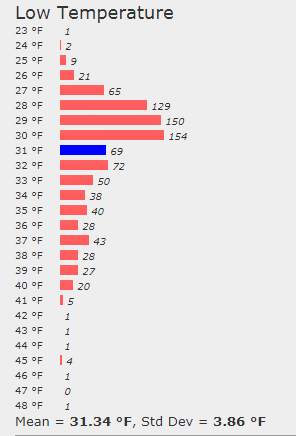

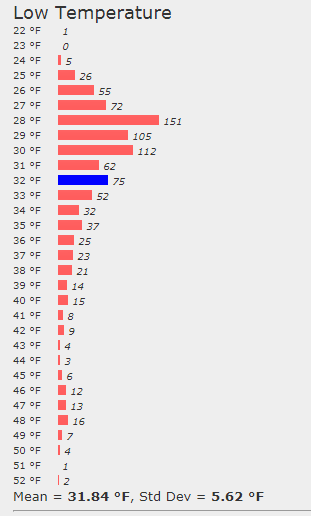

Now to what WxChallenge participants actually forecast. Below are the Day 2 and 3 min (low) temperature forecast distributions. While there were a good number of people who forecast close to MOS values, there were many more who didn't, including a whole host of entries in the mid and upper 30s.

In conclusion, some people will argue that MOS is "antiquated" and that better tools exist. And they're not completely wrong; post-processing techniques such as bias correction have shown substantial skill dealing with complex physical processes such as radiational cooling and surface fluxes. But it seems to me that with each passing year, more and more forecasters are relying on raw model output as forecast "truth", in part because of how easy the data is to find these days and how attractive it is to look at. And that's a runaway train that we will have trouble stopping, especially if it's what students are being taught in school.

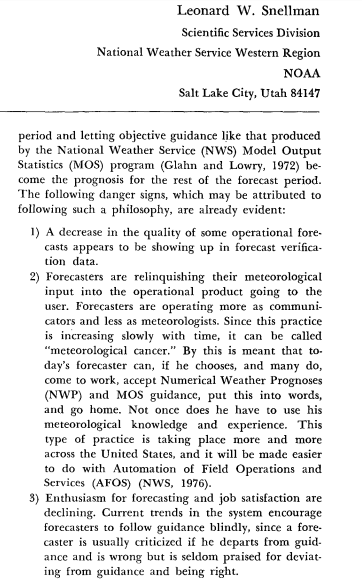

Former NWS forecaster Len Snellman (who I'm convinced was a time traveler) actually "forecast" (ha) this in 1977. He described it as "meteorological cancer", which if you've ever heard a Lance Bosart talk, probably rings a bell. I found the original Snellman article and posted a snippet below. It won't change where we're at, but it provides an interesting historical perspective. As for me, I'll continue to use MOS as my station forecast guidance until I retire to the Canadian vineyard/animal sanctuary, probably sooner rather than later :)

December 2016: The mental price of graduate school

Earlier this year I mentioned an article on Quartz titled "There's an awful cost to getting a PhD that no one talks about," where the author uses their own mental health struggles throughout their physics Ph.D. to make a broader point that poor mental health in academia, and particularly among graduate students, is an epidemic. Multiple studies have found that approximately 50% of graduate students suffer from depression, anxiety, or both (see a passage from the Quartz article below). There are a lot of factors that cause these types of rates: social isolation, imposter syndrome, holding oneself to perfectionist standards, and bullying/emotional abuse from superiors, quite often the graduate student's own supervisor. In this post, I'm mostly going to use my own experiences and those of others I know to discuss the last point.

It's been almost a decade since I started my Ph.D. I arrived in graduate school from a very competitive undergraduate program, so I was under few illusions that it was going to be easy. My Masters, which I completed in mid-2006, had gone relatively smoothly. It wasn't perfect, but thanks to a post-doc in my research group who started around the same time I did(and later became one of my best friends), I had a mentor aside from my thesis advisor who I could ask questions of without being mocked, who could help me with the technical aspects of research (code debugging, knowing what to look at next, etc.) that my advisor really couldn't help me with much. But what I didn't realize during my Masters is how much of a leap, mentally, emotionally, and scientifically, a Ph.D. was from that point. Part of the reason for this was that many of the things that make a Ph.D so tough: the comprehensive exam, the thesis proposal, even defending your work, was completely absent from my Masters program. I had no concept of how much of a leap it was, and was not anywhere close to being mentally prepared.

Our Ph.D program comprehensive exam was entirely oral. There was no written portion, no prepared notes or texts to study, no audience, no nothing. It was you and three faculty members basically asking any question they want in three sub-topics of your choosing. Some schools do it this way, some use written exams, some use a combination of both. Every place is different. I had studied for 2-3 weeks and thought I was prepared, especially since two of the topics were ones I felt confident in. Long story short, I wasn't prepared, not at all. It's somewhat of a blur to me now, but if I answered even half of the questions correctly, I'm remembering things in a positive light. In retrospect, they failed me and I deserved to fail. But that wasn't how I felt at the time; my reaction was largely emotional and irrational, thinking they failed me to "send a message" or as a "rite of passage." And even though I had another chance 3 months later, that was going to be it; fail the second time, and you get tossed out of the program.

The next 3 months were not pretty; my anxiety, which had mostly been in remission and under control for years, came back worse than ever. Completing simple tasks like walking down the street without panicking became tougher and tougher. I spent most of the 3 months oscillating between depression, anger, and paralyzing fear. I did end up passing the comprehensive exam the 2nd time, barely. But the damage was done. Five months after the initial failed exam, my mom had to fly 1500 miles to take me on a plane to visit her psychiatrist because I was too panicked to fly alone, even though I had done it many times.

I like to semi-joke that her psychiatrist saved my life. In reality, I never got to the point of suicidal thoughts. But through a combination of therapies, he made me functional again, and I stuck the Ph.D. thing out. There were other things later on: being told my initial journal manuscript draft was a piece of garbage that wasn't even written correctly enough to read it (to be fair, it wasn't written correctly), being told I had to start "hanging out with the right crowd" (never quite figured out who was the wrong crowd), spending the next 3 years thinking of myself as a mediocre student who never would stand out and just wanted to get out of academia.

Obviously, things change. My advisor and I developed a better relationship and never looked back once I explained to him how some of the things he said made me feel. We're good friends and colleagues to this day. I left academia briefly after graduation, but I came back pretty quickly and haven't left since. But you don't really ever forget how it feels.

My story is not unique. In fact, I don't even think it ranks that highly on the terrible grad school experience scale. I had friends whose advisors told them the first day they got there to "run this model and get me these results this week," when those friends had never run any model, much less within days and with no help. Since I transitioned from student to faculty, I've had former students and friends tell me about their own stories: Typically, it starts with an advisor whose expectations are unrealistic or too demanding, then come the demeaning comments that should count as emotional abuse but aren't usually reported because it's said by a superior or because you're supposed to "toughen up", and it spirals from there. There's the self-doubt, then there's the anxiety and/or depression, and then there's the struggle to get through it. Sometimes medication can help, sometimes medication can make it worse. It's hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel when you have trouble even walking down the street by yourself. This passage from the Quartz article is all too familiar:

So what can we do as mentors, colleagues, and friends of graduate students who suffer through this? I think the first thing is to realize it exists. Universities, graduate programs, faculty, they often have no concept of how difficult it is to be a graduate student: Sure, there's the computer programming, the research, the writing, but there's also the mental price that comes with all of these things. Second, it's not "tough" to stay quiet about your struggles or what/who caused them; that line of thinking needs to go. Departments, programs, and advisors need to be more aware and more accepting that these struggles are real, and that sometimes things THEY do are the root cause. Third, more resources need to be made available; university health centers are too quick to just prescribe medication that may or may not help. Student mental health charities such as Student Minds in the UK do exist, but more needs to be done. And more current students need to know that lots of former students (myself included) have gone through similar things, and are probably more willing to help or at least talk than they may think.

People often ask me "would you do your Ph.D. over again if you had the chance?", and my answer is "no, but I like my job." That answer is of course a paradox: The mental cost of my Ph.D. is not something I would choose to subject myself to again, but I wouldn't be able to have my current job if I hadn't. But more than anything, I hope grad students who go through similar or worse things just know that they're not alone, and there is actually a light at the end of the tunnel.

February 1, 2016: Bullying in Academia, part II

In December, I gave a short presentation at a departmental meeting entitled "Is bullying just a concern for children?". This post details some of the research I presented at that time. There was a good article in the Guardian in late 2014 that explained why bullying tends to thrive in higher education. Some excerpts are pasted below. Research has found that much of the faculty-faculty bullying in academia tends to take place when more senior faculty have something to gain by intimidating or feel threatened by their junior colleagues. As I mentioned in my previous post, I have at various times experienced both of these first-hand at other institutions.

Studies of how prevalent faculty-faculty bullying is differ in magnitude, but the results are pretty staggering. (http://bulliedacademics.blogspot.co.uk/2010/03/workplace-bullying-in-academia-canadian.html). A New Zealand study found that 65% of academics reported being bullied, while 38% reported it happened more than TEN TIMES in the past year (!!). A Canadian study reported 52%, with 21% saying they had experienced it for FIVE years or more. So who does the bullying, and what impacts does it cause? Read more below...

The stats above from the aforementioned Canadian survey show that peers and persons with power were responsible for the overwhelming majority of bullying of junior faculty members. This means that the bullies are indeed other faculty who feel that they have something to gain by trying to make one feel inferior. The problem is exacerbated by bullying victims often thinking that this is "part of the hierarchy" or "learning the ropes", when the reality is that it has an enormous impact on the victims' productivity, confidence, and overall happiness. The stats below from the same Canadian survey found that it affected both the quantity and quality of the bullied faculty members' work. Even more disturbing are the emotions reported by the bullied: Stress, frustration, anxiety, anger, and so on. This is not acceptable and should not continue to be accepted.

From personal experience and observations, I can say that affected faculty are often reluctant to go to people in charge (dept. chair, dean, etc.) out of fear they will be seen as snitches or, even worse, that the person-in-charge will be biased towards the more senior faculty member (having known them for a longer period of time). It is an endless cycle that is rarely addressed in an institutional or systematic way. So what can we do? Are there real steps we can take to improve these numbers? Read on for some suggestions...

There isn't one easy fix to academic bullying. Although many universities (including my own) have official policies that encourage the affected faculty to report bullying or related concerns to superiors and/or HR, studies have shown they rarely do. We need to establish resources for the affected persons that they feel will be fair and unbiased. Perhaps this requires committees or boards external to each department and/or college. Perhaps there are better suggestions out there. Whatever the exact solution, there needs to be an impartial resource that has some power to investigate and deal with these situations. Change will only come from the top when more affected faculty and academics are vocal about the things they've experienced and/or observed.

Finally: I may be part of faculty now, but it seems like yesterday that I was still a graduate student, stuck in a tunnel with only a faint light of a finished Ph.D. at the end. As much as faculty-faculty bullying is a legitimate problem, faculty-student bullying might legitimately be a bigger one. I encourage you to read the following article on the mental health costs of getting a Ph.D, and in my next post I will share some of my personal experiences and observations about graduate school. http://qz.com/547641/theres-an-awful-cost-to-getting-a-phd-that-no-one-talks-about/

December 1, 2015: bullying in academia, Part I

For my first blog post on my new website, I want to discuss an issue that has been close and important to me for over a decade: Bullying and harassment in academia. I suppose I should start by emphasizing that I have not experienced nor witnessed academic bullying or harassment at my current university, Embry-Riddle. In fact one of the primary reasons I came to work here was because I found most people work in a collaborative fashion, and most of all treat each other with respect and common (?) human decency.

I should also state that the things that I have experienced and witnessed in the past are hardly unique to me or to the physical sciences. And that pretty much says it all. A few months ago, Katie Mack, a Melbourne University physicist and astronaut, tweeted this: https://twitter.com/AstroKatie/status/610174867820797952

The fact that it got 400+ retweets, 600+ likes, and hundreds of replies points to the quiet epidemic in academia. Recently, a famous (infamous?) UC-Berkeley astronomer resigned because of years of sexual harassment claims that finally came to light (http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-uc-berkeley-astronomer-sexual-harassment-20151013-story.html) including the fact that the university essentially ignored these claims for years:

I think as a male scientist, I need to acknowledge that my experiences probably pale in comparison to many of my female counterparts. But I also think it's important that more of us speak to our experiences and put pressure on people in charge to slowly change this culture of bullying and abuse.

I will comment on faculty-student bullying in my next post. Today I want to focus on faculty-faculty bullying. Aside from sexual harassment (which is a huge issue that I don't feel qualified to speak to), the largest problems occur when more senior (typically tenured) faculty try to use their power to influence and/or control younger, generally non-tenured faculty. A few years ago when I had a contract (non-tenure track) assistant professor position, I ran into this type of situation. The last year of my contract, the permanent tenure-track position that I was temporarily occupying was opened up. I was told by more than one senior faculty member in my department that I would be a strong candidate for the position. What I did not know at the time was that the search committee chair was a person who had been on sabbatical the year I had been temporarily hired.

Long story short, I applied for the permanent position. I expected to be treated similarly to all other candidates. I was given a phone interview for which I was required to be outside the building I worked in. Although I found this to be slightly odd, I understood that it was likely just protocol. A few weeks later, I was sent a short form e-mail and snail mail letter saying I would no longer be considered for the tenure-track position. Considering these were my colleagues, there's a human decency argument to be made here, but that's besides the point. The letter was written by the department office manager and was not signed by any faculty member. Having already been through several faculty applications and searches, I recognized this not typical protocol and brought it up to the department chair. It turned out he had no idea that the letter had been sent or even written. Although I never completely found out the full story, I believe and continue to believe the search committee chair had the office manager type it up in a rush to rule me out as quickly as possible. In the end, it was for the best. It was a personality conflict and poisonous environment that I would not have enjoyed long-term, and of course it's entirely possible I was not a top-echelon candidate (although the fact that I was given an in-person interview at all 7 other schools I applied to, that seems unlikely). But it was how it was executed that is most important, namely:

- Two of the four search committee members were non-tenured (at the time) faculty who were co-PIs on active research grants with the tenured search committee chair. I have been told by multiple tenured faculty and department chairs that this is highly unusual and often forbidden.

- Agenda-driven actions (the snail mail letter written by the office manager in particular) that did not follow protocol.

And then...it got worse.

About six months later, as I was applying for the next round of open faculty positions, I was fortunate enough to be offered three tenure-track positions nearly simultaneously: Two in Florida that I ended up deciding between (one of which is my current job), and one at the rival school of my former employer. When the department chair of the rival school called me to offer me their position, he started out by telling me that "certain past behavior had been brought" to his attention. This "behavior" was a set of well-intentioned but misguided tweets I had made after the aforementioned search committee drama. In short, I felt the search committee chair was taking advantage of and bullying students who I had grown quite close to. In retrospect, it was stupid and immature to put this on social media and I did apologize to my department chair at that time.

However, six months had passed and this was another university. The tweets had been long deleted. So how did the rival school find out? Someone (almost certainly the aforementioned search committee chair) went out of his way to contact another university in the same state and "warn" them about my "behavior". Whether this was purely out of revenge/bitterness or the fact that he didn't want me working in the same state, or both, I probably will never know. But this type of thing happens ALL THE TIME, and needs to stop.

In short, we need to give junior faculty resources and a support system to combat more senior faculty from taking advantage of and/or bullying them. Junior faculty are the future of any university. If you treat them the way people should be treated (basic human decency), they will likely pass that on. And academia will subsequently become a brighter more welcoming place for faculty and students alike. This is not asking a lot. It's just asking for a start. And I'm asking for ideas from anyone who has them (milrads@erau.edu). Together, we can hopefully make a difference, however small that may be.